Generating electricity from sunlight is more practical than you might think. Germany is one of the world leaders in solar power production, and it gets less sunlight than most places in the northern United States. Energy prices continue to rise and the cost of solar panels keeps going down. If you want to go completely off-grid, solar is the most cost-effective way of generating your own electricity. And if you just want to reduce your electric bill and hedge your bets against rising electric rates, solar is probably the best option. Either way, solar power is a good investment for the homestead, as long as you think of it as a long-term investment. (For more about going off-grid, see my overview of renewable energy.)

Please be aware that even if you’re a do-it-yourselfer, installing a solar power system should be done only by qualified professionals, including a licensed electrician who’s familiar with all the codes and standards that pertain to solar power. We’re talking about electricity levels that can kill a person or cause a fire, so remember: safety first!

In fact, this topic is far too technical to cover thoroughly in one article. There are entire books written and courses offered on designing solar power systems, so if you’re planning to design your own system, get a book or take a course – preferably both. But for now, let’s look at what you can expect when you contact a solar energy provider.

Photovoltaic Basics

Photovoltaic (PV) panels convert light directly into electricity. (There are other ways to convert the sun’s energy into electricity, but those are more appropriate for utility-scale systems, not residential systems.) The most common PV panels are made of silicon, the same material that’s used to make computer chips; they offer the best balance between price and performance. Today’s panels are about 20% efficient, which means that 20% of the sunlight that hits the panel will be converted into electricity. The rest is turned to heat. That may not sound great, but remember that sunlight is free – you don’t have to mine it, drill for it, refine it, or transport it. (Side note: if you drive a gasoline-powered car, your engine is only 20% efficient and it uses fossil fuels and creates pollution. So don’t complain about solar panels, okay?) One solar panel doesn’t generate nearly enough for a house, so you’ll need a solar array – a group of panels wired together to produce a lot of energy.

Site Assessment

Before we design a PV system, we always conduct a thorough site assessment. This can start remotely, with the assessor asking you about your goals for your system. For example, do you want to generate all of the electricity that you need or just reduce your energy bill by generating some of your own electricity? If it’s the latter, about what percentage do you want to generate? And of course, what is your budget?

Next the assessor will conduct an electric load analysis to determine your electricity usage. This includes examining one or two years worth of electric bills and looking at the energy efficiency of your home and appliances. She will probably make recommendations for conserving electricity because it’s always less expensive to reduce consumption than to produce more.

A site assessment also includes a visual inspection of your property and roof (assuming you want the panels on your roof) to determine whether the roof can handle the added weight and stress of panels, where to place the panels for optimal production, and where to locate other equipment.

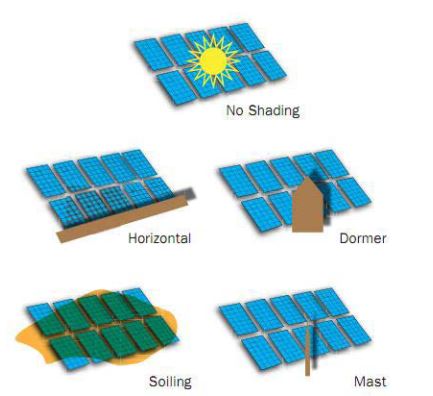

Next we perform a shading analysis. We start by getting data from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). This tells the sunlight that can be expected at a given location. It’s based on thirty years of weather data, so it takes into account your latitude as well as local cloud conditions. Once we know how much sunlight falls on the location itself, we look for the best place to locate the array, and we determine how shady it is at different times of day throughout the year. This helps estimate the actual production that you can expect from your system.

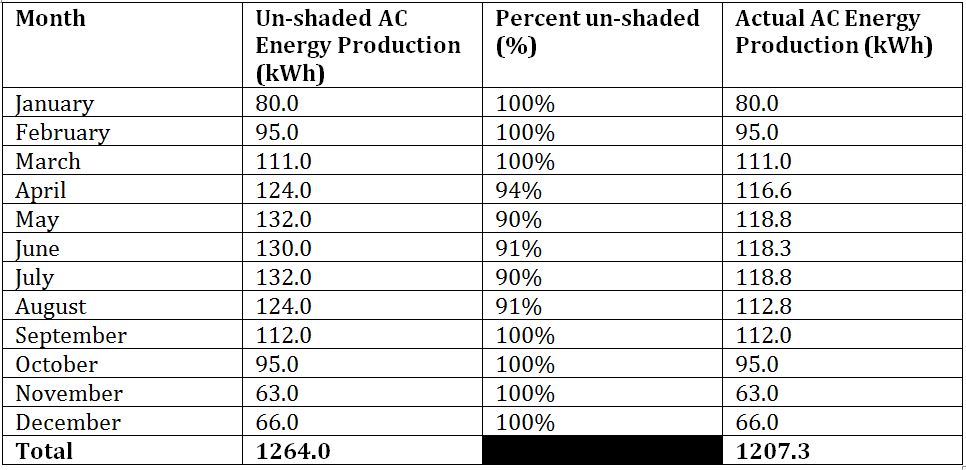

Here’s an example of a shading analysis report:

The unshaded AC energy production numbers (2nd column) come from NREL. As you can see, there’s less sunlight in the winter. That’s because the sun is lower to the horizon and the days are shorter. The percent unshaded (3rd column) is based on obstacles at your site, such as trees, buildings, chimneys, etc.

Speaking of south, in the northern hemisphere it’s common to point solar panels due south to capture the most sunlight throughout the day. That’s good for overall production, but if your power company charges more for electricity during peak hours, which usually happen in the mid to late afternoon, then you might find it beneficial to point your panels west. If your array will be roof mounted then you don’t have much choice, but don’t be discouraged if your roof faces east-west instead of south – you can still generate a lot of solar electricity.

Now that the assessor knows where the array will be located and its shading properties, she can determine the optimal size of the system so it gives you the amount of energy that you need. The design includes the number of panels and how they’ll be connected to each other, and what other components are needed and where they’ll go.

Cost Analysis

A site assessment also includes a cost analysis: how much will the system cost, how much money per year will you save on your electric bill, and how long will it take for the savings to balance out the cost of the system. The payback period is the amount of time it takes for the system to pay for itself. Depending on your location and your electric rate, a typical payback period may be somewhere between ten years and thirty years. (Remember when I said it’s a long-term investment?) The only reason we don’t have PV panels on our house is because we’re planning to relocate in about five years. Our next house is where we plan to retire, and you can bet that we’ll have a PV array on that one!

A cost analysis will also include a list of incentives and tax breaks that can help defray the cost of your system. In some cases, you could cut your cost in half by taking advantage of these incentives.

Power Purchase Agreements

A PV system could cost tens of thousands of dollars. If you don’t have that much money to invest, see if there are companies in your area that offer power purchase agreements (PPAs). With a PPA the company will install a PV system on your house at no cost to you, and you agree to pay them for the electricity that it generates, usually at a rate that’s much lower than your power company charges. They own and maintain the equipment, and you get a lower electric bill with no up-front costs. It’s a win-win for the consumer!

Well that’s a run-down of buying a PV system. Before signing any contracts, be sure the company is reputable, licensed, and insured. Get references if possible. They should do all of the steps that I’ve listed above, and also obtain the required permits, design and install the system, and schedule inspections before going live. If you get several estimates from competing companies, don’t just go with the lowest price – look for quality. You’re spending a lot of money on this, so stay involved in the process.

Do you have a PV system? Would you like to share your experience with us?

We will be off the grid when we build our new home here in California. Using passive solar design for our ICF home, a hybrid solar/tankless hot water heater, whole house fan with earth tubes and a masonry heater in the winter, we expect to be quite comfortable. Some of our family and friends think that we will be living in the “dark ages” when we tell them we will be off the grid, and are completely surprised when we explain that we can use a regular electric refrigerator (albeit an energy efficient one), run our satellite TV and a few laptops, along with a chest freezer in the basement without any problems! Heck, we can even have an electric garage door opener if we wanted one! We are also thinking of adding a wind generator once the house is built and the solar panels are off and running. Where our house will sit, if it’s stormy and cloudy, it’s generally windy, so why not benefit from both?! Besides, it will only cost a few hundred dollars more for our whole house solar system than it would to bring electrical lines to our house, so this decision was a no brainer for my husband and I.

Vickie,

Congratulations on going off grid! It sounds like you’ll have a nice house. (We’re jealous!)

One thing about wind on stormy days: it’s often too strong and too turbulent for the wind turbine. Every wind turbine has a maximum safe operating speed – beyond that, they’ll “furl” (turn the blades away from the wind) in order to protect themselves, or they’ll apply brakes in order to stop spinning. Either way, they aren’t generating power during windstorms. And turbulent winds cause stress on the turbine and the tower, often leading to premature failure.

For a turbine to generate a significant amount of energy, it needs to be on a very tall tower where it receives steady, non-turbulent winds. The rule of thumb is that the bottom of the blades should be at least 30 feet higher than the nearest object within 500 feet. A tower that tall could cost $10,000 or more, and that doesn’t include the cost of the turbine, wiring, etc.

I’m a big fan of wind power on a utility scale, but it rarely makes sense on a residential scale. If you’re going off grid, you’ll probably be using batteries for storage. For the money that a proper wind system would cost, you could put up more solar panels and a bigger battery bank.

Don’t let the turbine salespeople talk you into a turbine based on its maximum power output. Those numbers are “best case” and almost never occur in real life – certainly not on a sustained level. This is true regardless of whether it’s a traditional turbine design of a “revolutionary new design” (which are neither revolutionary or new).

Tom

All good things to know – thanks. Actually, we were going to build our own wind turbine with a used Chevy truck alternator, PVC pipe cut at angles for the blades, etc., following plans we saw in Mother Earth News. Yes, we plan to have quite a battery bank set up for our solar system, with a back-up generator just in case. Another use for the wind turbine would be to aerate our pond water, using the wind energy to draw water up a pipe and spray it out over the pond. Our property is situated on a ridge where cool air is drawn down the canyon at night and warm air goes up during the day, so there is usually a breeze toward the tops of the trees – especially between noon and five o’clock in the afternoon. I am aware of the costs to set up a commercial wind generator, however, we thought it might be fun to experiment making one of our own! 😀 Thanks for sharing your knowledge!

Tom – Thank you for this excellent overview of the solar assessment process. Very insightful and easy to understand. I work for a solar installer in PA (I can’t tell where you are from the article above) and even here in the Northeast US we get plenty of sun for solar installations to make financial sense. (In fact, NJ was second behind only California for new solar installations in 1st quarter of 2014!) Prices for installed systems have come down about 60-70% in the past 3 -4 years alone. One point about paying for the systems – if you get a home equity loan or LOC to pay for the system, your interest is (usually) tax deductible, the rates are ridiculously cheap right now, and your monthly payment will be less than what you would have paid the utility company for the electricity generated (at least here in PA and NJ). So you’re cash positive on Day One. In addition, you own the system so you’re not locking yourself into a long-term contract with a leasing or PPA company which might make selling your property more complicated down the road (the new owner of your property will have to have a good credit score and agree to assume the lease or PPA agreement themselves). The purchased system actually increases the value of your home (there are multiple studies from the west coast that are showing that now), so even if you plan on moving in the not so distant future, it can still make sense to install a solar PV system. You immediately replace your variable, ever-increasing (3 or 4% on average / year in the US) monthly utility payment with a fixed, loan payment that’s less than what you would have paid the utility company and will eventually end (when the loan is paid off). Your panels will then keep on producing for free essentially. Most panels have 25 year power production warranties and should actually keep producing for at least 35 or 40 years. I know that in some parts of the country electricity rates are a bit lower than they are here so the economics may be different elsewhere. The payback period for residential systems installed in NJ is about 4 – 6 years right now and in PA it’s about 6 – 9 years…depending on the size of the system (larger system, shorter payback). Thanks again for the informative article. Posting on our Facebook page! (Exact Solar!)

Thanks, DARA – very good information!

For those who want low initial investment, not necessarily complete self sufficiency, there is a company that overcomes most of the objections to startup solar called citizenre.org. If you have a qualifying utility, they so an energy survey, propose a system design, install and maintain a system and guarantee your current electric rate for 10 years. Its’ well thought out, including provisions for if you sell you place.

Eliminates the startup and maintenance costs and as rates rise you save because of the fixed rate. You can be pretty sure they’ll fix it when it needs it as your check will be going elsewhere if they don’t.

Basic requirements are a participating utility for backup electric, a phone line (to monitor the system), and some south facing area to install it on. Full details, including participating utilities, requirements, and an interactive map to see how many and where they have installed systems, to get some feedback from people actually using them, can be found on their site.

Thanks, Phil. What you described sounds like a PPA or a variation of that. Some offer rental or leased equipment, and with others it’s a rent-to-own scenario. In every case, they give a guaranteed electric rate for the agreement period.

Near as I can tell from a close examination Tom, this outfit owns the system, thus no upfront or recurring costs except the electric bill. I did some due diligence on the people behind it and they come up as legit. I usually attack things as the consumer from hell, but they seemed to have thought of most of the answers to potential questions/concerns. Worth a look anyway.

PS – Not clear from the site but I suspect where they make their money is in recouping any rebates, tax breaks and or sell backs to the utility. But even that business model counters the few stumbling blocks to selling the solar idea, upfront costs, the tax angles, which, while real people are reluctant to research and deal with even more paperwork on, the long amortization of owned systems, and the maintenance issue..which is a matter of self interest for the company.

If anyone interested in the above then

https://www.navitron.org.uk/forum/

Is a really good place to ask questions, a strange but really friendly bunch.

Thanks for the link, Tod!